A directional antenna has the ability to enhance reception of desired signals, while rejecting undesired signals arriving from slightly different directions. Although directivity normally means a beam antenna, or at least a rotatable dipole, there are certain types of antenna that allow fixed antennas to be both directive and variable. See Chap. 7 for fixed but variable directional antennas and Chap. 11 for fixed and non-variable directive arrays. Those antennas are transmitting antennas, but they work equally well for reception. This section shows a crude, but often effective, directional antenna that allows one to select the direction of reception with pin plugs or switches.

Consider Fig. 13-10. In this case, a number of quarter-wavelength radiators are fanned out from a common feedpoint at various angles from the building. At the near end of each element is a female banana jack. A pair of balanced feedlines from the receiver (300-Ω twin lead, or similar) are brought to the area where the antenna elements terminate. Each wire in the twin lead has a banana plug attached. By selecting which banana jack is plugged into which banana plug, you can select the directional pattern of the antenna. If the receiver is equipped with a balanced antenna input, then simply connect the other end of the twin lead direction to the receiver. Otherwise, use one of the couplers shown in Fig. 13-11.

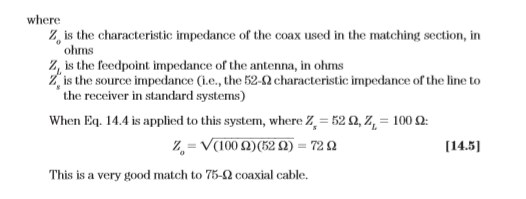

Figure 13-11A shows a balanced antenna coupler that is tuned to the frequency of reception. The coil is tuned to resonance by the interaction of the inductor and the capacitor. Antenna impedance is matched by selecting the taps on the inductor to which the feedline is attached. A simple RF broadband coupler is shown in Fig. 13-11B. This transformer is wound over a ferrite core, and consists of 12 to 24 turns of no. 26 enameled wire, with more turns being used for lower frequencies, and fewer for higher frequencies. Experiment with the number of turns in order to determine the correct value. Alternatively, use a 1:1 balun transformer instead of Fig. 13-11B; the type intended for amateur radio antennas is overkill powerwise, but it will work nicely.

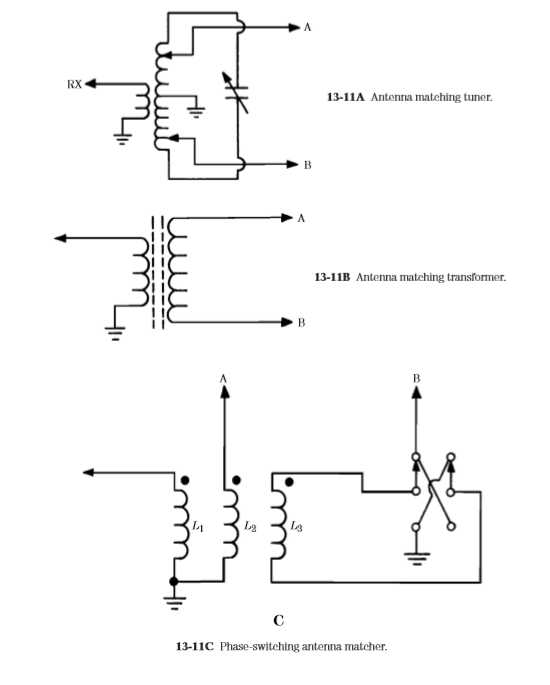

The antenna of Fig. 13-10 works by phasing the elements so as to null, or enhance (as needed), certain directions. This operation becomes a little more flexible if you build a phasing transformer, as shown in Fig. 13-11C and 13-11D. Windings L1, L2, and L3 are wound “trifilar” style onto a ferrite core. Use 14 turns of no. 26 enameled wire for each winding. The idea in this circuit is to feed one element from coil L2 in the same way all of the time. This port becomes the 0° phase reference. The other port, B, is fed from a reversible winding, so it can either be in phase or 180°out of phase with port A. Adjust the DPDT switch and the banana plugs of Fig. 13-10 for the best reception.