Find the best antennas for TV, radio, and wireless. Compare top antenna deals, use free antenna calculators, follow DIY guides, and buy high-performance antennas with confidence.

DIRECT CURRENT

OHM'S LAW

Resistor Networks

Resistor Networks: Complete Guide, Types, Calculations, and Applications

Resistor Networks are one of the most important and widely used building blocks in electronics. They appear in almost every electronic circuit, from simple voltage dividers to advanced digital-to-analog converters, microcontroller interfaces, radio frequency systems, and industrial control equipment.

A resistor network is not just a random collection of resistors. It is a carefully designed arrangement that allows engineers to control voltage, current, signal levels, impedance, and biasing with high precision. Understanding resistor networks is essential for students, hobbyists, technicians, and professional engineers.

In this comprehensive guide, we will explore what resistor networks are, how they work, the different types of resistor networks, their formulas, design considerations, real-world applications, and common mistakes to avoid.

What Are Resistor Networks?

Resistor networks are combinations of two or more resistors connected together in a specific configuration to achieve a desired electrical function. These resistors may be connected in series, parallel, or a mixture of both.

Instead of using individual resistors, engineers often use resistor networks to:

- Divide voltage accurately

- Control current flow

- Create reference voltages

- Set bias points for transistors and amplifiers

- Match impedances in signal paths

Resistor networks can be built using discrete resistors or manufactured as integrated resistor network packages (SIP, DIP, or surface-mount arrays).

Why Resistor Networks Are Important in Electronics

Resistor networks simplify circuit design and improve reliability. Instead of calculating and placing many individual resistors, a properly designed resistor network ensures consistent performance, better tolerance matching, and reduced circuit complexity.

Key benefits of resistor networks include:

- Improved accuracy due to matched resistors

- Reduced PCB space

- Lower assembly cost

- Better thermal stability

- Cleaner and more organized circuit layouts

Basic Types of Resistor Networks

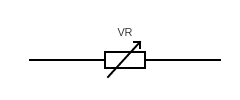

Resistor Network Schematics

Series Resistor Network

Parallel Resistor Network

Interactive Resistor Network Calculator

Calculate equivalent resistance for series or parallel resistor networks.

Result:

1. Series Resistor Networks

In a series resistor network, resistors are connected end-to-end so that the same current flows through each resistor.

Total resistance:

Rtotal = R1 + R2 + R3 + ...

Series resistor networks are commonly used in:

- Voltage divider circuits

- Current limiting

- High-voltage measurement systems

2. Parallel Resistor Networks

In a parallel resistor network, all resistors share the same voltage, but current divides among them.

Total resistance:

1 / Rtotal = 1 / R1 + 1 / R2 + 1 / R3 + ...

Parallel resistor networks are useful when:

- Lower resistance is required

- Current sharing is needed

- Power dissipation must be distributed

3. Series-Parallel Resistor Networks

Most real-world resistor networks are combinations of series and parallel connections. These networks allow designers to achieve precise resistance values that may not be available with standard resistor values.

Series-parallel resistor networks are common in:

- Analog signal conditioning

- Sensor interfaces

- Instrumentation circuits

Voltage Divider as a Resistor Network

One of the most common examples of resistor networks is the voltage divider. It consists of two or more resistors in series that divide an input voltage into smaller output voltages.

Voltage divider formula:

Vout = Vin × (R2 / (R1 + R2))

Voltage divider resistor networks are widely used in:

- Microcontroller ADC inputs

- Battery voltage monitoring

- Reference voltage generation

Ladder Resistor Networks

A ladder resistor network consists of repeating series and parallel resistor sections arranged in a ladder-like structure.

These resistor networks are used in:

- Digital-to-analog converters (DACs)

- Precision voltage scaling

- Audio attenuation circuits

Ladder resistor networks offer predictable voltage steps and excellent linearity when designed correctly.

R-2R Resistor Networks

The R-2R resistor network is one of the most famous resistor network configurations. It uses only two resistor values: R and 2R.

Despite its simplicity, the R-2R resistor network provides high accuracy and scalability, making it ideal for DAC applications.

Advantages of R-2R resistor networks:

- Only two resistor values required

- Excellent matching accuracy

- Easy integration into ICs

Integrated Resistor Network Packages

Modern electronics often use integrated resistor networks packaged in:

- SIP (Single Inline Package)

- DIP (Dual Inline Package)

- SMD resistor arrays

These packages contain multiple resistors with matched tolerances, improving performance in precision applications.

Applications of Resistor Networks

1. Microcontrollers and Embedded Systems

Resistor networks are used for pull-up and pull-down resistors, voltage dividers, and analog input conditioning.

2. Audio and Signal Processing

Audio mixers, attenuators, and filters rely heavily on resistor networks for signal shaping.

3. Power Electronics

In power supplies, resistor networks provide feedback sensing, voltage scaling, and protection functions.

4. RF and Communication Systems

Resistor networks are used in impedance matching, biasing RF amplifiers, and signal sampling.

Design Considerations for Resistor Networks

- Resistor tolerance and matching

- Power dissipation

- Thermal stability

- Noise performance

- Load interaction

Ignoring these factors can lead to inaccurate measurements, unstable circuits, or component failure.

Common Mistakes When Using Resistor Networks

- Using resistor networks as power supplies

- Ignoring load effects

- Using mismatched resistor tolerances

- Overlooking power ratings

Resistor Networks vs Individual Resistors

| Feature | Resistor Network | Individual Resistors |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | High (matched) | Moderate |

| PCB Space | Compact | Larger |

| Cost | Lower for multiple resistors | Higher assembly cost |

Future Trends in Resistor Networks

As electronics continue to miniaturize, resistor networks are becoming more integrated into ICs and system-on-chip designs. Advanced thin-film and laser-trimmed resistor networks are pushing accuracy and stability to new levels.

Conclusion

Resistor Networks are essential components in modern electronics. From simple voltage dividers to precision DACs and RF circuits, resistor networks provide reliable, scalable, and accurate solutions for controlling voltage and current.

By understanding resistor network types, calculations, and applications, you can design better, safer, and more efficient circuits. Whether you are a beginner or an experienced engineer, mastering resistor networks is a fundamental skill in electronics.

Recommended Resistor Network Components

Precision Resistor Network Arrays

For accurate resistor networks, matched resistor arrays provide better stability and tolerance than individual resistors.

- Vishay Precision Thin Film Resistor Network – Ideal for voltage dividers and DAC circuits

- Bourns SIP Resistor Network Pack – Perfect for microcontroller pull-up networks

Discrete Resistor Kits

- 1% Metal Film Resistor Kit (E12/E24) – Best for building custom resistor networks

An Active antenna for 160 to 4 meters

Active antennas rely on a combination of an antenna element (Such as a dipole, monopole, orloop) and anamplifier, which is the ‘active’ part. The antennaelementis non-resonant, and tends to be physically small. They have broad operating bandwidths, so don’t need to be tuned. In comparison, a resonant antenna would need tuner adjustments to cover the whole HF and lower VHF spectrum. So, the attraction of active antennas is convenience.

It is only fair to point out that some people dislike them, and there are pitfalls, which | shall point out. If you want a really excellent receiving antenna for all the HF amateur and broadcast bands, and have masses of space, why not put up a Beverage or rhombic antenna? If, as in my case, that’s out of the question, then consider an active antenna and, better still, try building your own! This one can be put together in a few hours and covers 160 to 4 metres.

DESIGN CONSIDERATIONS

My first homebrew active antenna was a dipole, and was quite successful. The main thing it taught me was thatit’s nota good idea to have too much gain. It is natural to conclude that, as a short antenna picks up a smaller signal than a resonant dipole, the gain must be made up in the amplifier. Being a broadband device, the amplifier is subjected to the entire HF radio spectrum including powerful broadcast transmitters. What tends to happen in practice is that it distorts, generating intermodulation products. These appear to the receiver as additional signals and, though giving the impression of a ‘lively’ receiving system, are entirely unwanted. An attenuator between the active antenna and receiver is of no use at all, if the distortion has already happened in the active antenna.

It occurred to me to try asingle wire monopole, which made for a simpler amplifier. This worked and has been in use ever since.

CIRCUIT DESCRIPTION

from a flat gain with frequency.

Build an Active Antenna

Let’s start by defining the word “active.” This does not suggest physical activity on the part of an electronic device. Rather, it tells us that the circuit is active in terms of voltage and current. A passive device, on the other hand, is a circuit that requires no operating voltage. It will exhibit some power loss as a signal is passed through it. Examples of passive devices are diode mixers, filters that use inductance and capacitance (LC filters) and all manner of wire antennas, etc.

An active mixer, on the other hand, uses a transistor or an IC, and operating voltage is applied to it. The mixer draws current and can cause a signal increase from the input to the output terminals. This is known as “conversion gain.” Active antennas contain RF amplifiers that require an operating voltage. Some active circuits may be designed to provide gain, while others may have unity gain (1) or a negative gain (signal loss). The nature of the active circuit depends upon its particular application.

Filters may be made active or passive. An active filter is often used to increase receiver selectivity at audio frequencies. This type of filter has no coils or inductors. Instead, it uses resistors, capacitors and ICs. An active filter may be designed for unity gain, or it may have a gain of 2 or 3, typically.

Active Antennas

What is an active antenna and why might we wish to build one? Active antennas are physically short, and they cover a wide spectrum of frequency. For example, an active antenna may perform uniformly from, say, 550 kHz to 50 MHz if it is designed well. This means that no antenna tuning or matching circuits are needed.

This type of antenna would be quite lossy if it did not include an RF amplifier section. In other words, if you connected a 6-foot whip antenna to your SW receiver and measured a 6.7MHzsignal at S3, that same signal might register 10 dB over S9 on your S meter if you switched to a full size dipole that was cut for 6.7 MHz. However, if we add an RF amplifier to the 6-foot whip before the signal is routed to the receiver, the S meter will indicate a similar reading to that when the dipole is used.

Why Use an Active Antenna?

Active antennas provide an alternative to no antenna at all if you are an apartment dweller or live in an urban area where external antennas are prohibited. These small active antennas are desirable for those who conduct business travel and find it necessary to stay in hotels or motels while on the road. The SWL need not be without an antenna if he is willing to build an active one

Figure 1: Schematic diagram of the active antenna amplifier. Capacitors without polarity marked are disc ceramic, 50 volts or greater. Resistors are 1/4 watt carbon composition or carbon film. RFC 1 and RFC 2 are miniature iron-core RF chokes (see text). JI and J2 are jacks of the builder's choice. Tl has 12 turns of no. 26 enam. wire (primary winding) on an Amidon Assoc. or FairRite FT-50-43 ferrite toroid core (850 mu). The secondary winding has six turns of no. 26 enam. wire wound uniformly over the primary winding. Overall amplifier gain is approx. 30 dB.

A Simple but Practical Active Antenna

Figure 1 contains a schematic diagram for an active antenna. The parts are inexpensive and easy to obtain. You can tack this circuit together in an evening. It may be constructed on a piece of perf board or a breadboard of your choice. The leads should be kept as short as practicable in order to ensure wide frequency coverage and the prevention of unwanted self-oscillations.

Qt is ajunction field-effect transistor (JFET). It has an input impedance of 1 megohm when wired as shown. This is an ideal situation when we attach a short antenna at JI]. You may use a long telescoping whip antenna, or a short hank of wire may be used. Any length from 6 to 10 feet is okay. Longer pieces of wire may be desirable for reception below 20 MHz. Don’t be afraid to experiment.

Q2 further amplifies the incoming signal (10 dB) and Q3 performs the same function, adding another 10 dB of gain. The gain of Q2 and Q3 may be as great as 15 dB per stage, depending upon the beta of the particular transistor plugged into the circuit. Q2 and Q3 operate as linear broadband amplifiers that use shunt and degenerative feedback. These two stages can be replaced by a single CA3028A or MC1350P IC, should you wish to do your own thing.

The output of Q3 is approximately 200 ohms. A 4:1 broadband step-down transformer (Tl) converts the 200-ohm output to 50 ohms. This makes it suitable for use with most shortwave and amateur receivers.

Although the circuit calls for a 12-V power supply, it will work well at 9V, should you wish to use a battery. Total current drain is on the order of 13 mA at 12 V, and it drops to 8 mA when the supply voltage is lowered to 9.

This circuit works well from 1.6 to 35 MHz. Operation at lower frequencies may be had by changing RCF1 and RFC2 to 10-mH units.

Using the Active Antenna

Connect a short antenna at J]. Vertical polarization will result if the wire or whip is vertical. Moving the antenna to a horizontal position will favor horizontally polarized signals. Be sure to experiment with the orientation of the antenna when monitoring different bands.

In an ideal situation the active antenna and its electronics would be located out of doors (on a balcony, deck or whatever). This will keep it away from electrical house wiring and steel frameworks if you live in an apartment. These man-made objects not only absorb signals but they may radiate noise. You may use RG-58 coaxial cable between the active antenna (T1) and your receiver. Any convenient length is suitable.

If you live near a powerful commercial broadcast station, a CBer with illegal power or an amateur radio station, you may find that the active antenna will overload and cause spurious signals across the tuning range of your receiver. This is a price that must be paid when a broadband circuit is used. Tuned circuits create needed selectivity for eliminating interference from nearby stations with strong signals. Active antennas do not contain tuned circuits.

Build the circuit in a metal box so that it is shielded. You should route the circuit ground to the metal box and ground the box to acold water pipe or an earth ground. This is not an essential action on your part, but it will help to improve the active antenna’s overall performance.

You may substitute 2N4416 FETs for the MPF102 shown at QI of Figure 1. Similarly, you may use 2N4400, 2N4401 or 2N5179 transistors at Q2 and Q3. The 1-mH RF chokes are available from your local store or other store.

=* by Doug Demaw, W1FB *=

Directional Antennas

How does a whole house surge protector work ?

What is a surge voltage ? How does it occur ?

Various types of surge voltages occur in electrical plants and electronic systems. They are differentiated mainly by their duration and power. Depending on the cause, a surge voltage can last a few hundred microseconds, hours or even days. The amplitude can range from a few millivolts to some ten thousand volts. The direct or indirect consequences of lightning strikes are one particular cause of surge voltages. Here, during the surge voltage, high surge currents with amplitudes of up to some ten thousand amperes can occur. In this case, the consequences are particularly serious. This is because the damaging effect first of all depends on the power of the respective surge voltage pulse.

The phenomenon of surge voltage

Every electrical device has a specific dielectric strength. If the level of a surge voltage exceeds this strength, malfunctions or damage can occur. Surge voltages in the high or kilovolt range are generally transient overvoltages of comparatively short duration. They generally last from a few hundred microseconds to a few milliseconds. As the maximum amplitude of such transients can amount to several kilovolts, steep voltage increases and differences are often the consequence. Surge protection is the only thing that helps. Indeed, the operator of an electrical system generally replaces the material damage to the system with corresponding protection. However, the difference in time between failure of the system to maintenance represents a risk in itself. This failure is often not covered by insurance and, within a short period of time, can become a heavy financial burden – especially in comparison to the cost of a lightning and surge protection concept.

This is how surge protection works

Surge protection should ensure that surge voltages cannot cause damage to installations, equipment or end devices. As such, surge protective devices (SPDs) chiefly fulfil two tasks: • Limit the surge voltage in terms of amplitude so that the dielectric strength of the device is not exceeded. • Discharge the surge currents associated with surge voltages. The way in which the surge protection works can be easily explained by means of the equipment's power supply diagram (Fig. 7). As described in Section 1.4, a surge voltage can arise either between the active conductors as normalmode voltage (Fig. 8) or between active conductors and the protective conductor or ground potential as common mode voltage (Fig. 9).

With this in mind, surge protective devices are installed either in parallel to the equipment, between the active conductors themselves (Fig. 10) or between the active conductors and the protective conductor (Fig. 11). A surge protective device functions in the same way as a switch that turns off the surge voltage for a brief time. By doing so, a sort of short circuit occurs; surge currents can flow to ground or to the supply network. The voltage difference is thereby restricted (Fig. 12 and 13). This short circuit of sorts only lasts for the duration of the surge voltage event, typically a few microseconds. The equipment to be protected is thereby safeguarded and continues to work unaffected.

Lightning and surge protection standards

National and international standards provide a guide to establishing a lightning and surge protection concept as well as the design of the individual protective devices. A distinction is made between the following protective measures: • Protective measures against lightning strike events: lightning protection standard IEC 62305 deals with this. A key component of this is an extensive risk assessment regarding the requirement, scope, and cost-effectiveness of a protection concept. • Protective measures against atmospheric influences or switching operations: IEC 60364-4-44 deals with this. In comparison with IEC 62305, it is based on a shortened risk analysis and uses this as the basis for deriving corresponding measures. In addition to the standards mentioned, if applicable, other legal and country- specific stipulations are also to be considered.

What is the basic principle of antenna?

An antenna is defined by Webster‘s Dictionary as ―a usually metallic device (as a rod or wire) for radiating or receiving radio waves.‖ The IEEE Standard Definitions of Terms for Antennas (IEEE Std 145–1983) defines the antenna or aerial as ―a means for radiating or receiving radio waves.‖ In other words the antenna is the transitional structure between free-space and a guiding device. The guiding device or transmission line may take the form of a coaxial line or a hollow pipe (waveguide), and it is used to transport electromagnetic energy from the transmitting source to the antenna or from the antenna to the receiver. In the former case, we have a transmitting antenna and in the latter a receiving antenna.

An antenna is basically a transducer. It converts radio frequency (RF) signal into an electromagnetic (EM) wave of the same frequency. It forms a part of transmitter as well as the receiver circuits. Its equivalent circuit is characterized by the presence of resistance, inductance, and capacitance. The current produces a magnetic field and a charge produces an electrostatic field. These two in turn create an induction field.

Definition of antenna

An antenna can be defined in the following different ways:

1. An antenna may be a piece of conducting material in the form of a wire, rod or any other shape with excitation.

2. An antenna is a source or radiator of electromagnetic waves.

3. An antenna is a sensor of electromagnetic waves.

4. An antenna is a transducer.

5. An antenna is an impedance matching device.

6. An antenna is a coupler between a generator and space or vice-versa.

source : https://www.sathyabama.ac.in/sites/default/files/course-material/2020-10/SEC1301.pdf

Electromagnetic Radiation

Electromagnetic Radiation is energy in the form of a wave of oscillating electric and magnetic fields, the wave travels through a vacuum at a velocity of 2.998 x 10^8 meters per second (186,284 miles per second). The Wavelength of an electromagnetic wave determines its properties , x-rays , infrared , microwaves , radio waves and light are electromagnetic radiation.

WAVELENGTH

What Is Electromagnetic Radiation?

The Nature of Electromagnetic Waves

The Electromagnetic Spectrum

Properties of Electromagnetic Radiation

How Electromagnetic Radiation Works

Receiver for Fiber-Optic IR Extender

There are various types of remote-control extenders. Many of them use an electrical or electromagnetic link to carry the signal from one room to the next. Here we use a fibre-optic cable. The advantage of this is that the thin fibre-optic cable is easier to hide than a 75-Q coaxial cable, for example. An optical link also does not generate any additional radiation or broadcast interference signals to the surroundings. We use Toslink modules for connecting the receiver to the transmitter. This is not the cheapest solution, but it does keep everything compact. You can use a few metres of inexpensive plastic fibreoptic cable, instead of standard optical cable for interconnecting digital audio equipment. The circuit has been tested using ten metres of inexpensive plastic fibre-optic cable between the receiver and the transmitter (which is described elsewhere in this issue).

The circuit is simplicity itself. A standard IR receiver/demodulator (IC1, an SFH506) directly drives the Toslink transmitter IC2. We have used the RC5 frequency of 36 kHz, but other standards and frequencies could also be used. Both ICs are well decoupled, in order to keep the interference to the receiver as low as possible. Since the Toslink transmitter draws a fairly large current (around 20 mA), a small mains adapter should be used as the power source. There is a small printed circuit board layout for this circuit, which includes a standard 5-V supply with reverse polarity protection (D2). LED Dl is the power-on indicator. The supply voltage may lie between 9 and 30 V. In the absence of an IR signal, the output of IC1 is always High, and the LED in IC2 is always on. This makes it easy for the transmitter unit to detect whether the receiver unit is switched on. The PCB shown here is unfortunately not available readymade through the Publishers' Readers Services.

source : https://archive.org/details/ElektorCircuitCollections20002014/page/n13/mode/2up?view=theater

Transmitter for Fibre-Optic IR Extender

This circuit restores the original modulation of the signal received from the remote-control unit, which was demodulated by the receiver unit at the other end of the extender (see 'Receiver for fibre-optic IR extender').

If no signal is received, the Toslink transmitter in the receiver is active, so a High level is present at the output of the Toslink receiver in this circuit. Buffer IC2a then indicates via LED Dl that the receiver unit is active. The received data are re-modulated using counter IC3, which is a 74HCT4040 since the Toslink module has a TTL output. In the idle state, IC3 is held continuously reset by IC1. The oscillator built around IC2c runs free. When the output of the Toslink receiver goes Low, the counter is allowed to count and a carrier frequency is generated. This frequency is determined by the oscillator frequency and the selected division factor. Here, as with the receiver, we assume the use of RC5 coding, so a combination has been chosen that yields exactly 36 kHz. The oscillator frequency is divided by 2 9 on pin 12 of the counter, and 18.432 MHz 2 9 = 36 kHz. The circuit board layout has a double row of contacts to allow various division factors to be selected, in order to make the circuit universal. You can thus select a suitable combination for other standards, possibly along with using a different crystal frequency. The selected output is connected to four inverters wired in parallel, which together deliver the drive current for the IR LEDs D3 and D4 (around 50 mA). A signal from the counter is also indicate that data are being transmitted, via LED D2. This has essentially the opposite function of LED Dl, which goes out when D2 is blinking. In the oscillator, capacitor C3 is used instead of the usual resistor to compensate for the delay in IC2c. As a rule, this capacitor is needed above 6 MHz. It should have the same value as C load of the crystal, or in other words 0.5C1 (where CI = C2). At lower frequencies, a lkQ to 2kQ2 resistor can be used in place of C3.

A yellow LED is used for the power-on indicator D5. The current through this LED is somewhat higher than that of the other LEDs. If you use a red high-efficiency LED instead, R5 can be increased to around 3kQ3.

The circuit draws approximately 41 mA in the idle state when the receiver is on. If the receiver is switched off, the transmitter emits light continuously, and the current consumption rises to around 67 mA.

The PCB shown here is unfortunately not available readymade through the Publishers' Readers Services.

source : https://archive.org/details/ElektorCircuitCollections20002014/page/n1/mode/2up?view=theater

Electronic Stethoscope

In order to listen to your heartbeat you would normally use a listening tube or stethoscope. This circuit uses a piezo sounder from a musical greetings card or melody generator, as a microphone. This transducer has an output signal in the order of 100 mV and its low frequency response is governed by the input impedance of the amplifier. For this reason we have chosen to use an emitter follower transistor amplifier. This has a high input impedance and ensures that the transducer will have a very low frequency response. At the output you just need to connect a set of low impedance headphones to be able to listen to your heartbeat.

Replacing the emitter follower with a Darlington transistor configuration will further increase the input impedance of the amplifier.

source : https://archive.org/details/ElektorCircuitCollections20002014/page/n3/mode/2up?view=theater

DIY Front Panel Foils

It is fairly easy to produce professionally looking, permanent front panel foils ('decals') for use on electronic equipment if you have a PC available along with an inkjet printer ( or similar). Plus, of course, matt transparent sheet of the self-adhesive type as used, for instance, to protect book covers. This type of foil may be found in stationery shops or even the odd building market. One foil brand the author has used successfully goes by the name of Foglia Transparent. The production sequence is basically as follows:

1. The decal is designed at true size (1:1 or 100%) with a graphics program or a word processor, and then printed in black and white on a sheet of white paper (do not use the colour ink cartridge). Allow the ink to dry. Cut the foil as required, then pull the adhesive sheet from the paper carrier sheet. Keep the carrier paper handy, it will be used in the next phase.

2. Once the ink has dried, the transparent foil is placed on top of the decal. The foil is lightly pressed and then slowly pulled off the paper again (see photograph). Because the adhesive absorbs the ink to a certain extent, the mirror image of the decal artwork is transferred to the adhesive side of the foil.

3. For further processing, first secure the foil on the carrier paper again. Next, cut the decal to the exact size as required by the equipment front panel. Finally, pull off the carrier sheet again and apply the transparent foil on to the metal or plastic surface.

source : https://archive.org/details/ElektorCircuitCollections20002014/page/n13/mode/2up?view=theater

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

%20and%20Earth.png)