Figure 9-5 shows the true resonant longwire antenna. It is a horizontal antenna, and if properly installed, it is not simply attached to a convenient support (as is true with the random length antenna). Rather, the longwire is installed horizontally like a dipole. The ends are supported (dipole-like) from standard end insulators and rope.

The feedpoint of the longwire is one end, so we expect to see a voltage antinode where the feeder is attached. For this reason we do not use coaxial cable, but rather either parallel transmission line (also sometimes called open-air line or some such name), or 450-Ωtwin lead. The transmission line is excited from any of several types of balanced antenna tuning unit (see Fig. 9-5). Alternatively, a standard antenna tuning unit (designed for coaxial cable) can be used if a 4:1 balun transformer is used between the output of the tuner and the input of the feedline. What does “many wavelengths” mean? That depends upon just what you want the antenna to do. Figure 9-6 shows a fact about the longwire that excites many users of longwires: It has gain! Although a two-wavelength antenna only has a slight gain over a dipole; the longer the antenna, the greater the gain. In fact, it is possible to obtain gain figures greater than a three-element beam using a longwire, but only at nine or ten wavelengths.

What does this mean? One wavelength is 984/FMHz ft, so at 10 m (29 MHz) one wavelength is about 34 ft; at 75 m (3.8 MHz) one wavelength is 259 ft long. In order to meet the two-wavelength criterion a 10-m antenna need only be 68 ft long, while a 75-m antenna would be 518 ft long! For a ten-wavelength antenna, therefore, we would need 340 ft for 10 m; and for 75 m, we would need nearly 2,600 ft. Ah me, now you see why the longwire is not more popular. The physical length of a nonterminated resonant longwire is on the order of

Of course, there are always people like my buddy (now deceased) John Thorne, K4NFU. He lived near Austin, TX on a multiacre farmette that has a 1400ft property line along one side. John installed a 1300 ft longwire and found it worked excitingly well. He fed the thing with homebrew 450-Ω parallel (open-air) line and a Matchbox antenna tuner. John’s longwire had an extremely low angle of radiation, so he regularly (much to my chagrin on my small suburban lot) worked ZL, VK, and other Southeast Asia and Pacific basin DX, with only 100 W from a Kenwood transceiver.

Oddly enough, John also found a little bitty problem with the longwire that textbooks and articles rarely mention: electrostatic fields build up a high-voltage dc charge on longwire antennas! Thunderstorms as far as 20 mi away produce serious levels of electrostatic fields, and those fields can cause a buildup of electrical charge on the antenna conductor. The electric charge can cause damage to the receiver. John solved the problem by using a resistor at one end to ground. The “resistor” is composed of ten to twenty 10-MΩ resistors at 2 W each. This resistor bleeds off the charge, preventing damage to the receiver.

A common misconception about longwire antennas concerns the normal radiation pattern of these antennas. I have heard amateurs, on the air, claim that the maximum radiation for the longwire is

1. Broadside (i.e., 90°) with respect to the wire run or

2. In line with the wire run

Neither is correct, although ordinary intuition would seem to indicate one or the other. Figure 9-7 shows the approximate radiation pattern of a longwire when viewed from above. There are four main lobes of radiation from the longwire (A, B, C, and D). There are also two or more (in some cases many) minor lobes (E and F) in the antenna pattern. The radiation angle with respect to the wire run (G–H) is a function of the number of wavelengths found along the wire. Also, the number and extent of the minor lobes is also a function of the length of the wire.

Complete free tutorial antennas design , diy antenna , booster antenna, filter antenna , software antenna , free practical antenna book download !

Quad Beam Antennas

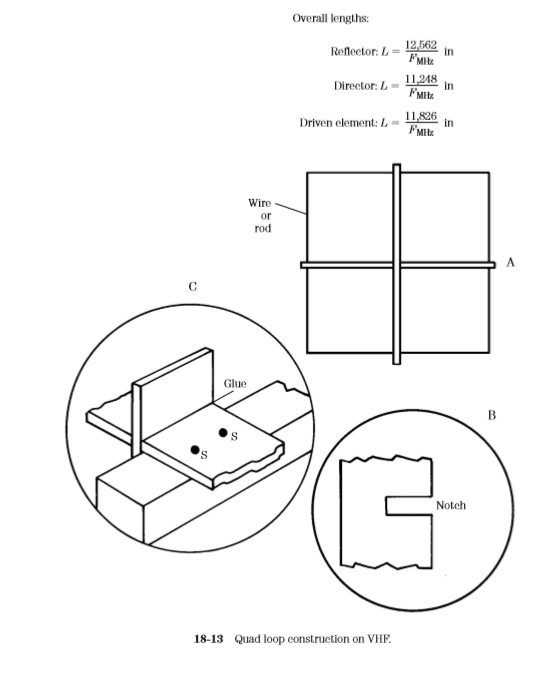

The quad antenna was introduced in the chapter on beams. It is, nonetheless, also emerging as a very good VHF/UHF antenna. It should go without saying that the antenna is a lot easier to construct at VHF/UHF frequencies than it is at HF frequencies! Figure 18-13 shows a modest example.

There are several methods for building the quad antenna, and Fig. 18-13 represents only one of them. The radiator element can be any of several materials, including heavy solid wire (no. 8 to no. 12), tubing, or metal rods. The overall lengths of the elements are given by:

There are several alternatives for making the supports for the radiator. Because of the lightweight construction, almost any method can be adapted for this purpose.

In the case shown in Fig. 18-13, the spreaders are made from either 1-in furring strips, trim strips, or (at above 2 m) even wooden paint stirring sticks. The sticks are cut to length, and then half-notched in the center (Fig. 18-13, detail B).

The two spreaders for each element are joined together at right angles and glued (Fig. 18-13, detail C). The spreaders can be fastened to the wooden boom at points S in detail C. The usual rules regarding element spacing (0.15 to 0.31 wavelength) are followed.

See the information on quad antennas in Chap. 12 for further details. Quads have been successfully built for all amateur bands up to 1296 MHz.

Reference : Practical Antenna Handbook - Joseph P. Carr

Halo Antennas

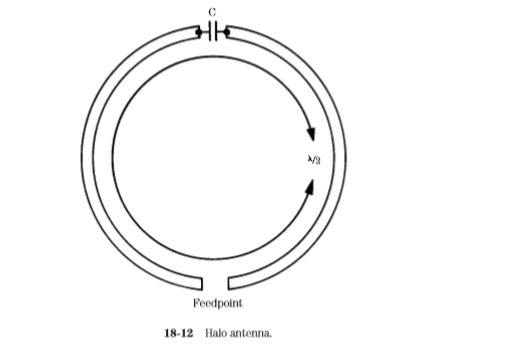

One of the more saintly antennas used on the VHF boards is the halo (Fig. 18-12). This antenna basically takes a half-wavelength dipole and bends it into a circle.

The ends of the dipole are separated by a capacitor. In some cases, a transmitting-type mica “button” capacitor is used, but in others (and perhaps more commonly), the halo capacitor consists of two 3-in disks separated by a plastic dielectric.

While air also serves as a good (and perhaps better) dielectric, the use of plastic allows mechanical rigidity to the system.

(source : Practical Antenna Handbook by Joseph J. Carr)

Groundplane Antennas

The groundplane antenna is a vertical radiator situated above an artificial RF ground consisting of quarter-wavelength radiators. Groundplane antennas can be either 1⁄4-wavelength or 5⁄8-wavelength (although for the latter case impedance matching is needed—see the previous example).

Figure 18-11 shows how to construct an extremely simple groundplane antenna for 2 m and above. The construction is too lightweight for 6-m antennas (in general), because the element lengths on 6-m antennas are long enough to make their weight too great for this type of construction. The base of the antenna is a single SO-239 chassis-type coaxial connector. Be sure to use the type that requires four small machine screws to hold it to the chassis, and not the single-nut variety.

The radiator element is a piece of 3⁄16-in or 4-mm brass tubing. This tubing can be bought at hobby stores that sell airplanes and other models. The sizes quoted just happen to fit over the center pin of an SO-239 with only a slight tap from a lightweight hammer—and I do mean slight tap. If the inside of the tubing and the connector pin are pretinned with solder, then sweat soldering the joint will make a good electrical connection that is resistant to weathering. Cover the joint with clear lacquer spray for added protection.

The radials are also made of tubing. Alternatively, rods can also be used for this purpose. At least four radials are needed for a proper antenna (only one is shown in Fig. 18-11). This number is optimum because they are attached to the SO-239 mounting holes, and there are only four holes. Flatten one end of the radial, and drill a small hole in the center of the flattened area. Mount the radial to the SO-239 using small hardware (4-40, etc.).

The SO-239 can be attached to a metal L bracket. While it is easy to fabricate such a bracket, it is also possible to buy suitable brackets in any well-equipped hardware store. While shopping at one do-it-yourself type of store, I found several reasonable candidate brackets. The bracket is attached to a length of 2 2-in lumber that serves as the mast.

J Pole Antennas

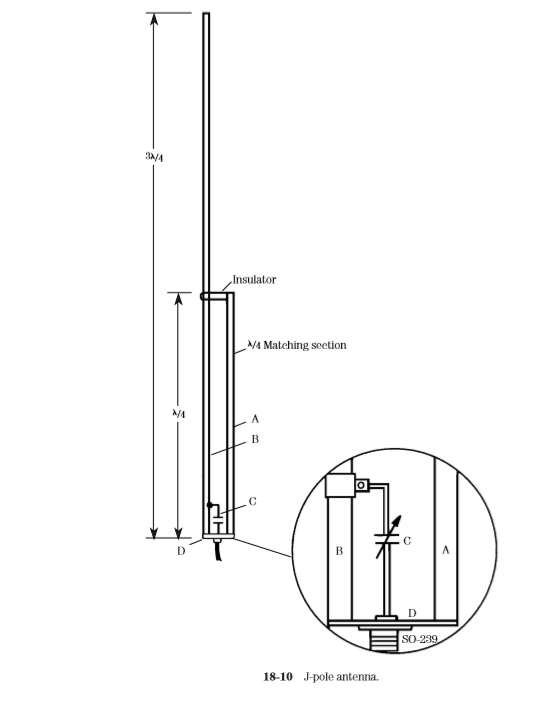

The J-pole antenna is another popular form of vertical on the VHF bands. It can be used at almost any frequency, although the example shown in Fig. 18-10 is for 2 m. The antenna radiator is 3⁄4-wavelength long, so its dimension is found from

Taken together the matching section and the radiator form a parallel transmission line with a characteristic impedance that is 4 times the coaxial cable impedance. If 50-Ω coax is used, and the elements are made from 0.5 in OD pipe, then a spacing of 1.5 in will yield an impedance of about 200 Ω. Impedance matching is accomplished by a gamma match consisting of a 25-pF variable capacitor, connected by a clamp to the radiator, about 6 in (experiment with placement) above the base.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)